Implementation details

In this section, we will discuss the techniques and technologies used to implement the system.

Rust features

Ownership & borrowing

Ownership is a set of rules that govern how a Rust program manages memory, it enables Rust to make memory safety guarantees without needing a garbage collector. Ownership’s rules are the following:

- Each value in Rust has an owner.

- There can only be one owner at a time.

- When the owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped.

Most of the time, we’d like to access data without taking ownership of it. To accomplish this, Rust uses a borrowing mechanism. Instead of passing objects by value (T), objects can be passed by reference (&T).

Below is an example taken from the form rufi_core::core::vm::round_vm::round_vm module. The struct VMStatus has a neighbor defined as Option<i32> and we want to return its reference without losing ownership of it:

pub fn neighbor(&self) -> &Option<i32> {

&self.status.neighbor

}

Function overload

Rust does not support function overloading, so given the following snippet of code:

pub fn new() -> Self {

Self {

slots: vec![],

}

}

pub fn new(slots: Vec<Slot>) -> Self {

let mut reversed_slots = slots;

reversed_slots.reverse();

Self {

slots: reversed_slots,

}

}

you will get the following error:

error[E0592]: duplicate definitions with name `new`

A possible solution for this problem is to remove the second constructor and implement the From trait. This is a basic mechanism to convert between different types:

impl From<Vec<Slot>> for Path {

fn from(slots: Vec<Slot>) -> Self {

let mut reversed_slots = slots;

reversed_slots.reverse();

Self {

slots: reversed_slots,

}

}

}

Lifetimes

A lifetime is a construct the compiler uses to ensure all borrows are valid. Specifically, a variable’s lifetime begins when it is created and ends when it is destroyed. As a reference lifetime 'static indicates that the data pointed to by the reference lives for the entire lifetime of the running program.

In the following code snippet:

pub fn register_root<A: 'static + Copy>(&mut self, v: A) {

self.export_data().put(Path::new(), || v);

}

if we remove the 'static lifetime we get the following error:

error[E0310]: the parameter type `A` may not live long enough

Smart pointers

In the following code snippet, we see that the HashMap’s value type is defined as Box<dyn Any>:

pub struct Export {

pub(crate) map: HashMap<Path, Box<dyn Any>>,

}

Why not use Any directly? The dyn keyword is used to highlight that calls to methods on the associated Trait are dynamically dispatched. Box is a smart pointer: boxes allow you to store data on the heap rather than the stack. What remains on the stack is the pointer to the heap data. In this case, we use Box because we have a type whose size can’t be known at compile time, and we want to use a value of that type in a context that requires an exact size.

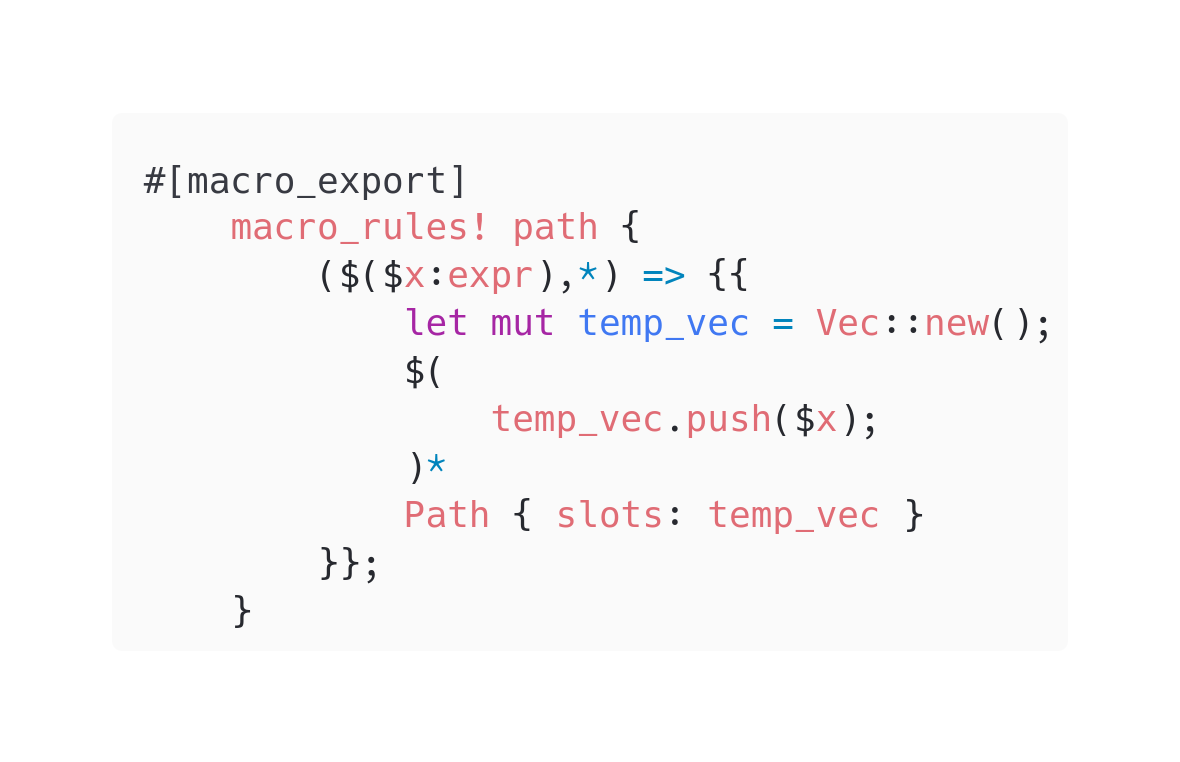

Macros

Fundamentally, macros are a way of writing code that writes other code, which is known as meta-programming.

Scala features

Given Instances

Given instances define canonical values of certain types that serve for synthesizing arguments to context parameters, defined by the using clause, letting the synthesis of repetitive arguments in functions. In our project, this mechanism is used instead of Scala 2’s implicits.

Here’s an example of a function that utilizes context parameters:

def fold[A](f: Field[A])(aggr: (A, A) => A)(using d: Defaultable[A]): A =

fold(f)(d.default)(aggr)

The given instances of this context parameter can be brought to scope by importing nameOfTheObject.given.

Self Types

Self-types are a way to declare that a trait must be mixed into another trait, even though it doesn’t directly extend it. That makes the members of the dependency available without imports. This mechanism is utilized through the entirety of the ScaFi-fields and ScaFi-core modules to perform dependency injection between traits.

Here are a few examples:

trait Builtins:

self: Language =>

import Builtins.given

//code that uses Language functions

trait Fields:

self: FieldCalculusSyntax =>

//code that uses FieldCalculusSyntax features

Type Classes

A type class is an abstract, parameterized type that lets you add new behavior to any closed data type without using sub-typing. This concept can be useful for:

- Expressing how a type you don’t own—from the standard library or a third-party library—conforms to such behavior

- Expressing such behavior for multiple types without involving sub-typing relationships between those types

Here’s an example of a type class used inside ScaFi-fields:

trait Defaultable[A]:

def default: A

Here we defined, for all the A’s that implement this type class, an added behavior of specifying a default value, such as 0 for Int or List. empty for List. This concept is useful when defining a Field since a default value is used when querying the field for a value of a device that is not present inside the device map.

We can define implicit type class implementations through the given mechanism as we did with the cats.Monad type class:

given Monad[Field] with

override def pure[A](x: A): Field[A] =

...

override def flatMap[A, B](fa: Field[A])(f: A => Field[B]): Field[B] =

...

override def tailRecM[A, B](a: A)(

func: A => Field[Either[A, B]]

): Field[B] =

...

With this given instance, we can make our Field act like a monad wherever the given instance is in scope. This is particularly useful for utilizing Fields inside for comprehension constructs.

Integration layer between RuFi-core and ScaFi-core

Based on the solutions analyzed in the “Detailed design” chapter, various attempts have been made to implement the integration layer between RuFi-core and ScaFi-core. In any case, it was decided to take advantage of the interoperability of Scala Native and Rust with C.

The experimentation carried out has led to partial successes in some cases, while in others it has highlighted the limitations of the interoperability of the languages.

A particular success case that must be mentioned is the one in which a higher-order function was passed from Scala to Rust. A specific repository is provided for the details of this case: scala-native-rust-interoperability-example.

For details on the limitations encountered during the interoperability experimentation, a specific section is provided in the “Implementation issues” chapter.

Of the two solutions analyzed in the “Detailed design” chapter, the one in which a fully interoperable implementation of RuFi-core with C is provided was more effective and less problematic. However, due to the aforementioned issues, it was not possible to provide a complete and working implementation of this design choice.